|

Eagles may get exposed to a neurotoxin through their prey. MIKE MARTIN By Erik Stokstad — Mar. 25, 2021

More than 25 years ago, biologists in Arkansas began to report dozens of bald eagles paralyzed, convulsing, or dead. Their brains were pocked with lesions never seen before in eagles. The disease was soon found in other birds across the southeastern United States. Eventually, researchers linked the deaths to a new species of cyanobacteria growing on an invasive aquatic weed that is spreading across the country. The problem persists, with the disease detected regularly in a few birds, yet the culprit’s chemical weapon has remained unknown. Today in Science, a team identifies a novel neurotoxin produced by the cyanobacteria and shows that it harms not just birds, but fish and invertebrates, too. “This research is a very, very impressive piece of scientific detective work,” says microbiologist Susanna Wood of the Cawthron Institute. An unusual feature of the toxic molecule is the presence of bromine, which is scarce in lakes and rarely found in cyanobacteria. One possible explanation: the cyanobacteria produce the toxin from a bromide-containing herbicide that lake managers use to control the weed. The discovery highlights the threat of toxic cyanobacteria that grow in sediment and on plants, Wood says, where routine water quality monitoring might miss them. The finding also equips researchers to survey lakes, wildlife, and other cyanobacteria for the new toxin. “It will be very useful,” says Judy Westrick, a chemist who studies cyanobacterial toxins at Wayne State University and was not involved in the new research. “I started jumping because I got so excited.” Wildlife biologists with U.S. Geological Survey and local institutions first detected the eagles’ brain disease, now called vacuolar myelinopathy, at DeGray Lake in Arkansas in late 1994. They soon learned that coots and owls at the lake were dying with similar brain lesions. The researchers ruled out industrial pollutants and infectious disease, and they couldn’t find any algal toxins in the water. Then funding ran out, and the scientists turned to other projects. But Susan Wilde, an aquatic ecologist at the University of Georgia, Athens, persisted, with intermittent funding. “I just had a lot of colleagues and graduate students that were self-propelled to work on this.” Birds were dying at lakes and reservoirs throughout the southeast, and at every lake her team visited, they found Hydrilla verticillata, a tough and fast-growing invasive plant. In 2001, Wilde noticed dark spots on the underside of the leaves. Back in the lab, she put a sample under a microscope and shone light that makes cyanobacteria glow red. The whole leaf lit up. “I was running around the hallways,” Wilde recalls. “It was kind of a eureka moment.” The cyanobacterium was a new species, which Wilde named Aetokthonos hydrillicola in 2014. She suspected it was producing a neurotoxin. To confirm that hunch, Wilde and colleagues fed hydrilla to mallards in the lab. Only those that ate leaves harboring the cyanobacteria developed brain lesions. Next, a group led by Timo Niedermeyer, a natural products chemist at Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg, figured out how to culture the cyanobacterium and initially found that the lab-grown strain did not cause lesions in chickens. “Huge disappointment,” he recalls. But when they added bromide salts to the culture medium, the cyanobacteria began to produce the neurotoxin. In further tests, Wilde and colleagues found that the toxin also kills fish, insects, and worms. “This is a really potent neurotoxin, even at fairly low levels,” she says. Wilde suspects mammals are also vulnerable; her colleagues hope to test the compound on mice. Niedermeyer’s lab discovered the neurotoxin was fat-soluble, which is unusual for cyanobacterial toxins and suggests it can accumulate in tissues. Fish and birds are exposed when they eat hydrilla coated with the new species of cyanobacteria, and then the toxin may move through the food web as eagles and owls consume afflicted prey. “If verified, bioaccumulation has important consequences to the whole ecosystem and human health” if people consume toxin-contaminated fish or waterfowl, says Kaarina Sivonen, a microbiologist at the University of Helsinki. The cyanobacterium appears to get the bromide it needs to make the toxin from hydrilla, which can concentrate bromide from lake sediment in its leaves. Bromides are rare in freshwater, but they could be eroding from rocks, or they might originate from coal-fired power plants. Other sources could include brominated flame retardants, fracking fluids, and road salt. Wilde suspects one local source might be an herbicide, diquat dibromide, that is used to kill hydrilla. Wilde points to recent success managing the weed without chemicals, by stocking lakes with fish that eat hydrilla. Although grass carp are not desirable for fishing, using sterile carp would ensure the population would die out once its work was done. The Army Corps of Engineers has already released the fish into a reservoir on the border of Georgia and South Carolina, where they removed the hydrilla. Since then, no more sick eagles have been found. Saving the birds from the neurotoxin will be a long fight, however, because both hydrilla and the cyanobacteria are exceptionally hardy. The invasive plant is likely to continue to be spread by boats, researchers say, and perhaps also migrating birds. “We should expect the cyanobacterium to follow,” says George Bullerjahn, a microbiologist at Bowling Green State University, “and the threat of toxicity to become a broader issue.”

Can one of the fastest-developing regions in the country prioritize conservation? That's the hope of the ambitious Great Springs Project, which has inched a little closer to realizing its goal of a national parklike trail connecting two of Texas' most populous cities.

On Dec. 8, the National Park Service selected the Great Springs Project to receive backing in the form of "community planning and technical assistance" for their endeavor to build a network of multiuse trails from Austin to San Antonio. The project proposes adding 50,000 acres of protected land over the Edwards Aquifer recharge zone and portions of the contributing zones in Hays, Travis, Comal, and Bexar counties, as well as connecting hike-and-bike trails to the project's namesake four bodies of water: Barton Springs, San Marcos Springs, Comal Springs, and San Antonio Springs. The southeast boundary of the imagined spring-to-spring trail clings closely to the west of I-35 and its northwest boundary spans along Barton Creek, Onion Creek, and the Blanco River down to San Antonio. The legal mechanism by which this land would be protected in perpetuity is called a conservation easement, in which private landowners get tax cuts in return for ceding their right to develop on the land. But typically the land in those cases is not publicly accessible; Great Springs, conversely, wants to encourage public access to the trails and waterways the same way a state park might. Co-founded in 2018 by Deborah Morin, former board member of the Hill Country Foundation, the project aims to protect endangered species and Hill Country water quality from the increasing development along that corridor, especially in Hays County, one of the fastest-growing counties in the U.S. But Great Springs leadership also contends that it will be an "economic development catalyst," creating jobs with its ambitious construction. "We know that more people in Central Texas means we need more places here for those people to live, work, and be outside," says Emma Lindrose-Siegel, their chief development officer. "For that reason, Great Springs Project works with developers and city and county planners to ensure that the things we love most about living here will be protected and continue to be a resource for future generations." The project is currently in its design stages, so there's no clear plan yet as to where the trails will go, but Lindrose-Siegel says they will potentially connect to existing trails, making transportation by bike all the way from Austin to San Antonio a possibility. However much this project aims to involve the human communities along I-35, she says that only "a small amount of the total land conserved will have actual trail on it ... A priority is protecting the habitat of endangered species endemic to our region." So far, Great Springs has made their pitch to former San Antonio Mayor Phil Hardberger, who told the San Antonio Report that the plan is "conceptually" possible, though he worries that the public access part of it could make deals with landowners more difficult to attain. Hill Country landowners might live on their plots and be averse to bike trails crossing through their private land, but there are many different types of easements, and in many cases the landowners benefit from negotiating different uses for the land. For example, Shield Ranch, northwest of Austin, hosts summer camps and partners with TerraPurezza regenerative farm to raise their sheep and pigs on the ranch's property. Easements like this allow the family that owns the land large tax cuts to be able to keep the homestead in perpetuity, while allowing other uses on other parts of the property – a win-win situation that Great Springs could take advantage of. GSP currently partners with Hill Country Conservancy, Meadows Center for the Environment, San Marcos Greenbelt Alliance, Activate SA, Comal Trails Alliance, and Hill Country Alliance, and Lindrose-Siegel says they do want to "collaborate with ... city and county governments and community groups to both amplify their work and unite conservation efforts." Great Springs is still just in its nascency; to help get the project off the ground, they'll require large philanthropic donations, and probably federal dollars, too. The trail planning process is projected to be finished in 2021, but in order to actually break ground, they first need to seek conservation easements and partnerships with land trusts and local, state, and national parks – and, of course, that all-important funding. Congress Provides New Funding for the First Time in Nearly 10 Years

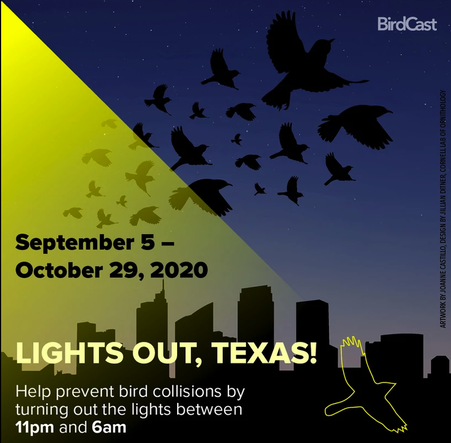

Scenic America celebrates the inclusion of $16 million in funding for the National Scenic Byways Program in the omnibus spending package announced today by Congress—the first time in nine years that dedicated funds have been made available for this important program. As part of the FY 2021 appropriations bill, the funds will deliver a welcome economic boost to the thousands of communities throughout the country located along these more than 1,000 transportation corridors. Scenic America worked with several lawmakers in leading the charge to ensure the byways program’s inclusion in the appropriations bill. “We are grateful to Chairwoman Susan Collins (R-ME) for her leadership role in securing these funds and commend Sen. Jack Reed (D-RI) for his leadership and support for the funding in the Senate FY 21 Transportation and Housing Appropriations process to help reopen funding for the National Scenic Byways Program,” said Scenic America President Mark Falzone. “We are also greatly appreciative to Chairman David Price (D-NC) and Rep. Mario Diaz-Balart (R-FL) for support of the program throughout the Conference. This is an important program that preserves and protects our most significant roadways while bringing economic benefits to communities along the way.” “Maine’s National Scenic Byways and the Acadia All-American Road provide Mainers and tourists alike with spectacular views and memorable experiences. These roadways also spur much-needed economic activity throughout our state,” said Senator Collins. “Last year, Senator [Ben] Cardin (D-MD) and I led bipartisan legislation that reopened the National Scenic Byways program to allow for new roads to be nominated and designated. This funding included in the omnibus will help to protect precious corridors and provide tangible benefits for local communities.” Established in 1991, the National Scenic Byways Program recognizes roadways with notable scenic, historic, cultural, natural, recreational, and archaeological qualities. The funding included in this spending package is available to the 150 roadways that carry this national distinction, as well as to the more than 1,000 state and tribal scenic byways throughout the country. Beyond their conservation and environmental benefits, scenic byways are a critical part of America’s travel and tourism industry, which generated $2.9 trillion in economic impact in 2019, according to the U.S. Travel Association. For example, the Blue Ridge Parkway generated $1.4 billion in economic output and supported 16,300 jobs in North Carolina and Virginia in 2019, according to the National Park Service. During the same year, the Natchez Trace Scenic Parkway brought $13.1 million in economic output to Alabama, Tennessee, and Mississippi, supporting 161 jobs. In 2019, Scenic America took the lead in working with Congress to reinvigorate the National Scenic Byways Program, both to open new nominations and establish funding for the program. Since 2009, no new byways had been designated by the Federal Highway Administration and funding was cut off in 2012. The Reviving America’s Scenic Byways Act was signed into law on September 22, 2019, thanks to the leadership of bill sponsors Rep. David Cicilline (D-RI), Sen. Collins, Rep. Garret Graves (R-LA), and Sen. Cardin. “The bill’s lead sponsors recognized that the Byways Program could deliver tremendous benefits and acted quickly to move this legislation through Congress,” added Falzone. “We also want to thank co-sponsors Rep. Chris Pappas (D-NH), Rep. Harley Rouda (D-CA), Sen. Jeanne Shaheen (D-NH), Sen. Christopher Coons (D-DE), Sen. Angus King (I-ME), Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI), Sen. Chris Van Hollen (D-MD) and Sen. Maggie Hassan (D-NH).” Scenic America will continue to advocate for the program’s long-term funding, as well as for it to be included in the Surface Transportation Reauthorization bill that Congress will take up next session. Lights Out, Texas!Texas Conservation Alliance is teaming up with the Dallas Zoo, the Perot Museum, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, and others to share the message of Lights Out, Texas!, September 5 through October 29, 2020.

Visit birdcast.info to learn more about bird migration patterns.The peak migration season this year for birds traveling south to warmer winter climates is between September 5 and October 29. Bright commercial and residential lights at night cause birds to become disoriented and distracted. The second greatest source of mortality for migratory birds (behind feral cats) is collisions with building windows and walls. Birds are easily confused and disoriented by artificial light at night. TCA and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology are partnering on an initiative called, “Lights Out, Texas!”. All Texans can take simple action to protect birds during peak migration (Sept 5-Oct 29) – just be sure your lighting is off or minimal. It’s as easy as the flick of a switch! |

Contact UsFollow us on Facebook and YouTube

|