WATER & DROUGHT

“As you get more global warming, you should see an increase in the extremes of the hydrological cycle – droughts and floods and heavy precipitation.” — James Hansen

Lest We Forget: Precious Water is Vital!

by Frank Dietz, for the H-Z February 3, 2024

How wondrous has been our recent drought-denting rainfall! With more winter in front of us, “it’s fresh

like Spring.” The pastures and our yard where we live are finally green. May 2024 be notably wet.

My first Texas employment was in “Aggieland” located in Brazos County. Among many interesting folk

was a young faculty person at Texas A&M who also served as a specialist with the Extension Service

(now AgriLife). In a presentation to rural and small-town pastors the specialist spoke to us about “Aqua

Amnesia.” As a native of New Orleans and years growing up on the Gulf Coast, I found it curious to hear

about how frustratingly dry things can be in Texas. The presenter convincingly described the 1950’s of

his adolescence when the A&M campus and much of Texas were scorched to a crisp with little

vegetation surviving. He got a laughing response when he said, “our sacred Kyle Field where football

rules was a standout exhibit of green amidst all the brown surroundings.” He pointed out that in the

late 1960’s a vast hurricane had “greened up” just about everything. The concern he expressed was that

measures that were undertaken during drought times and even legislation to address water deficits

“evaporated” rapidly in a state of “aqua amnesia.” Many rushed back to old consumption practices for

irrigation, drilling, industrial, and household uses as if it was a time for “no worry” going forward.

We can hope that the recently dry riverbeds of our Texas Hill Country and dropping water tables will not

be ignored going forward. I raise this, in part, in response to a number of our own Comal County

readers and neighbors asking me if I’d say something about the wells going dry, the periodic interruption

of well flows, dry or trickling in our assumed wonderfully vigorous springs and more. There commenced

discussions about coaxing folks to utilize landscaping practices and household water consumption with

greater measures of stewarding our water supplies. More general questions were initiated about how

to use more prudent practices in the rapid development of Comal County and the neighboring Hill

Country region. When a group of folks with well worries spoke of how long they would wait before a

drilling service could extend the depth of their wells or drill a new well, discussions deepened. Might

the licensing process be examined for greater cautionary measures? Would the drillers be willing to tell

us anecdotally if not scientifically what they are seeing and encountering when they tell customers

about their waiting lists? What discussions might be underway with policy making elected and staff

officials that address our water precariousness? Might we begin acknowledging “right to capture”

principles require some reiteration in light of the population swell and so many more “taking” from our

finite water sources?

Let’s begin with planting/sowing less thirsty choices. Let’s look to newer measures for recycling much

used water. Let’s explore what some innovators describe and demonstrate as ONE WATER buildings.

Consider pervious rather than impervious cover whenever possible in your own space as well as in our

public and commercial spaces. The lists go on!

How my life circumstances have taken me on a water journey! As a youngster, I watched adults pound

pipes into sandy soil to “find water.” Now I wonder how deep some with mighty drills must reach. Let’s

talk together rather than allow our Springs and much more to go dry.

like Spring.” The pastures and our yard where we live are finally green. May 2024 be notably wet.

My first Texas employment was in “Aggieland” located in Brazos County. Among many interesting folk

was a young faculty person at Texas A&M who also served as a specialist with the Extension Service

(now AgriLife). In a presentation to rural and small-town pastors the specialist spoke to us about “Aqua

Amnesia.” As a native of New Orleans and years growing up on the Gulf Coast, I found it curious to hear

about how frustratingly dry things can be in Texas. The presenter convincingly described the 1950’s of

his adolescence when the A&M campus and much of Texas were scorched to a crisp with little

vegetation surviving. He got a laughing response when he said, “our sacred Kyle Field where football

rules was a standout exhibit of green amidst all the brown surroundings.” He pointed out that in the

late 1960’s a vast hurricane had “greened up” just about everything. The concern he expressed was that

measures that were undertaken during drought times and even legislation to address water deficits

“evaporated” rapidly in a state of “aqua amnesia.” Many rushed back to old consumption practices for

irrigation, drilling, industrial, and household uses as if it was a time for “no worry” going forward.

We can hope that the recently dry riverbeds of our Texas Hill Country and dropping water tables will not

be ignored going forward. I raise this, in part, in response to a number of our own Comal County

readers and neighbors asking me if I’d say something about the wells going dry, the periodic interruption

of well flows, dry or trickling in our assumed wonderfully vigorous springs and more. There commenced

discussions about coaxing folks to utilize landscaping practices and household water consumption with

greater measures of stewarding our water supplies. More general questions were initiated about how

to use more prudent practices in the rapid development of Comal County and the neighboring Hill

Country region. When a group of folks with well worries spoke of how long they would wait before a

drilling service could extend the depth of their wells or drill a new well, discussions deepened. Might

the licensing process be examined for greater cautionary measures? Would the drillers be willing to tell

us anecdotally if not scientifically what they are seeing and encountering when they tell customers

about their waiting lists? What discussions might be underway with policy making elected and staff

officials that address our water precariousness? Might we begin acknowledging “right to capture”

principles require some reiteration in light of the population swell and so many more “taking” from our

finite water sources?

Let’s begin with planting/sowing less thirsty choices. Let’s look to newer measures for recycling much

used water. Let’s explore what some innovators describe and demonstrate as ONE WATER buildings.

Consider pervious rather than impervious cover whenever possible in your own space as well as in our

public and commercial spaces. The lists go on!

How my life circumstances have taken me on a water journey! As a youngster, I watched adults pound

pipes into sandy soil to “find water.” Now I wonder how deep some with mighty drills must reach. Let’s

talk together rather than allow our Springs and much more to go dry.

Before and after photos show dire conditions at popular swimming hole Jacob’s Well

By Mary Claire Patton

Published August 2, 2023 (Source)

Swimming hasn’t been allowed at Jacob’s Well for the past two summers and newly posted photos of the spring-fed swimming hole make it clear why the Hill Country hot spot has been closed.

Hays County officials, who shared photos of a dried-up creek bed with KSAT on Tuesday, announced last summer that Jacob’s Well would be closed for swimming for the “foreseeable future.” In April, they said swimming will remain a no-go due to water levels and spring flow.

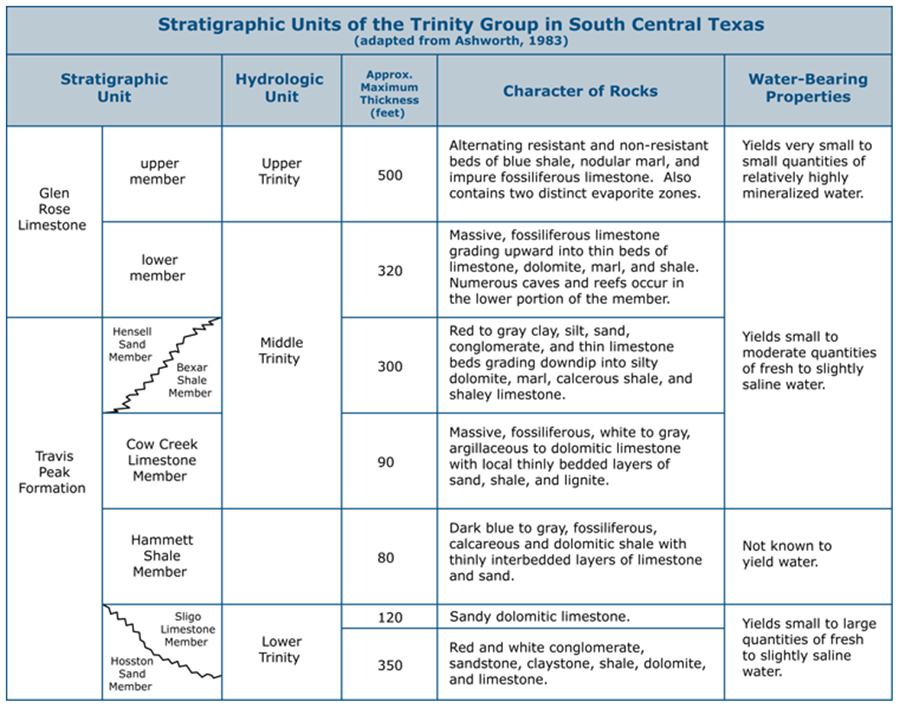

Under normal conditions, Jacob’s Well releases thousands of gallons of water every day from the Trinity Aquifer, which comes from an extensive underground cave system, according to Hays County Parks officials.

However, the lack of rainfall coupled with some of the hottest summer months on record have all but dried up the famous swimming hole.

The Watershed Association, a local nonprofit organization that keeps Jacob’s Well and the headwaters of Cypress Creek, clean, clear and flowing, posted an update on social media over the weekend stating that the spring is measuring at zero flow for the sixth time since 2000.

“There are multiple factors contributing to Jacob’s Well’s near-dry condition, and it’s crucial to recognize that it’s not just one issue at play,” Watershed officials said.

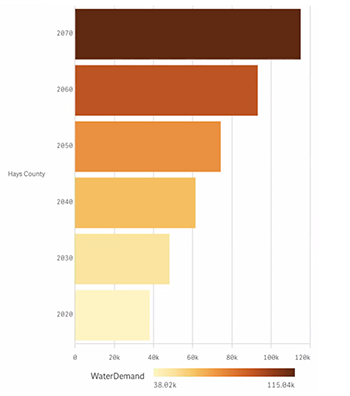

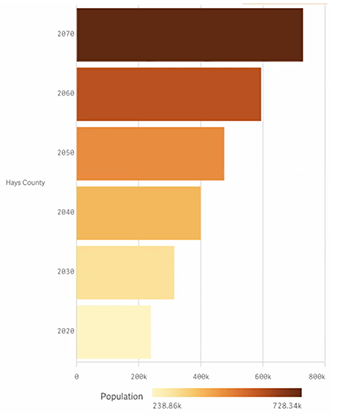

They also mentioned the extreme and exceptional drought conditions Central Texas has been experiencing the past few years and added that “increased groundwater demand to accommodate rapid population growth is resulting in more and more water being withdrawn in Woodcreek North, across the region.”

Anthony Shepherd of the Hays County Parks Department told KSAT on Tuesday that Jacob’s Well will remain closed for swimming for the foreseeable future.

“We are still open for visitors to come view the well and hike our trails, but no water access will be permitted,” Shepherd said.

KSAT has reached out the Hays County officials regarding the over-pumping of groundwater in the area.

Published August 2, 2023 (Source)

Swimming hasn’t been allowed at Jacob’s Well for the past two summers and newly posted photos of the spring-fed swimming hole make it clear why the Hill Country hot spot has been closed.

Hays County officials, who shared photos of a dried-up creek bed with KSAT on Tuesday, announced last summer that Jacob’s Well would be closed for swimming for the “foreseeable future.” In April, they said swimming will remain a no-go due to water levels and spring flow.

Under normal conditions, Jacob’s Well releases thousands of gallons of water every day from the Trinity Aquifer, which comes from an extensive underground cave system, according to Hays County Parks officials.

However, the lack of rainfall coupled with some of the hottest summer months on record have all but dried up the famous swimming hole.

The Watershed Association, a local nonprofit organization that keeps Jacob’s Well and the headwaters of Cypress Creek, clean, clear and flowing, posted an update on social media over the weekend stating that the spring is measuring at zero flow for the sixth time since 2000.

“There are multiple factors contributing to Jacob’s Well’s near-dry condition, and it’s crucial to recognize that it’s not just one issue at play,” Watershed officials said.

They also mentioned the extreme and exceptional drought conditions Central Texas has been experiencing the past few years and added that “increased groundwater demand to accommodate rapid population growth is resulting in more and more water being withdrawn in Woodcreek North, across the region.”

Anthony Shepherd of the Hays County Parks Department told KSAT on Tuesday that Jacob’s Well will remain closed for swimming for the foreseeable future.

“We are still open for visitors to come view the well and hike our trails, but no water access will be permitted,” Shepherd said.

KSAT has reached out the Hays County officials regarding the over-pumping of groundwater in the area.

'It's heartbreaking': Jacob's Well stops flowing for sixth time in recorded history

By Maya Fawaz (Photo by Michael Minasi)

Published August 2, 2023 (Source)

Jacob's Well, the popular spring-fed swimming hole in Wimberley, has reached zero flow for the sixth time in its recorded history. All six of those times have occurred in the last 23 years — and it's become more frequent.

Earlier this summer, the Hays County park announced Jacob's Well had low flow and would likely not open for swimming. Now, its flow has stopped entirely.

David Baker, executive director of the nonprofit The Watershed Association, has worked to protect the well and the surrounding natural environment for almost 30 years. He said this is the worst he’s ever seen it.

“It's heartbreaking,” he said. “We've worked so hard. The community has invested lots of money in buying up land to protect it.”

Low water levels at Jacob’s Well have been a recurring issue, and experts say the well’s health is an indicator of the region’s water supply. Baker says more water is taken out of the aquifers each year and not enough is going back in to recharge them.

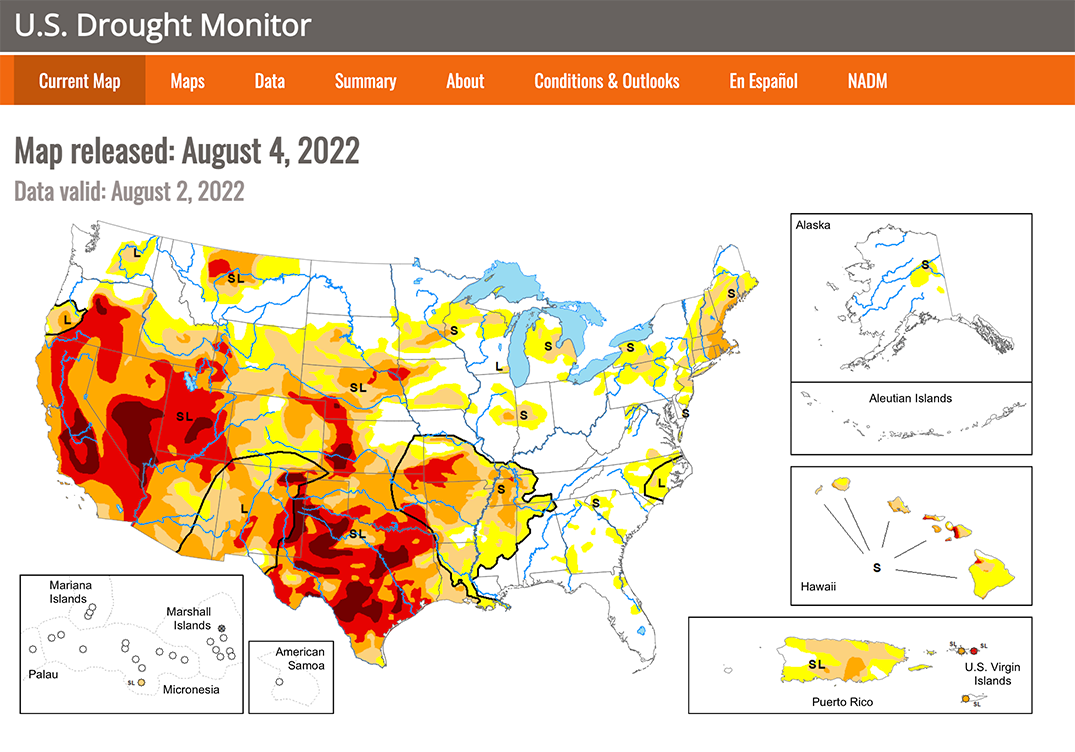

“There’s no water flowing out of the creek at all,” Baker said. “We're still in a very severe extreme drought here in Central Texas. You look at the drought monitor and you'll see that big, dark brown circle there in the middle of Texas.”

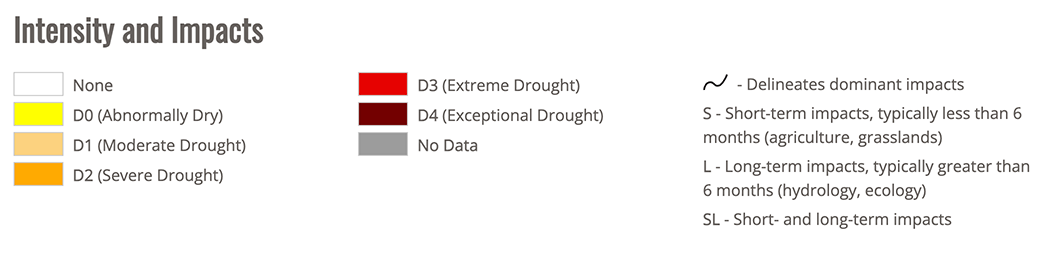

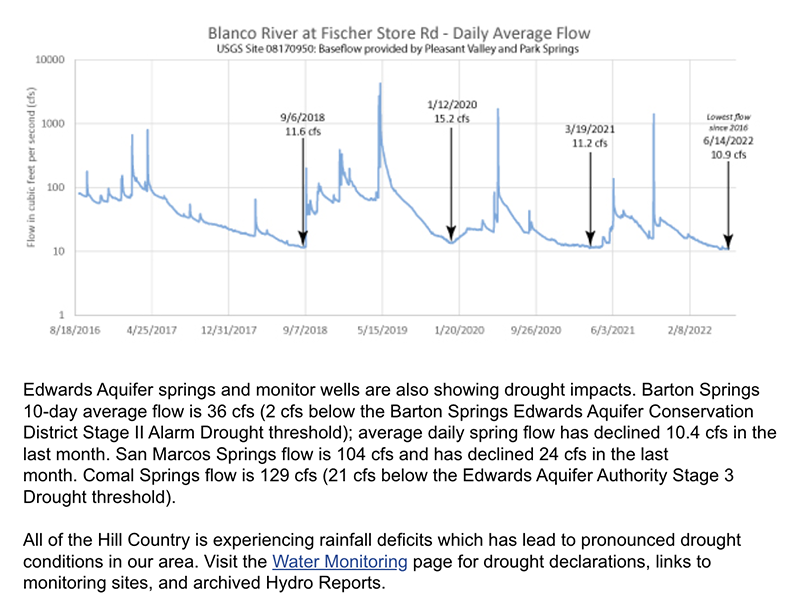

The City of Wimberley entered Stage 4 drought conditions on Tuesday. The Hays Trinity Groundwater Conservation District will need to decrease its water use district-wide by 40% — and by 30% within the Jacob’s Well Groundwater Management Zone. The district says both the Pedernales and Blanco rivers are experiencing record-low flows.

“It's really an ecological disaster, it's an economic disaster,” Baker said. “The county has lost hundreds of thousands of dollars in revenue from not being able to allow swimmers there for the past two summers.”

Blue Hole Regional Park, another nearby swimming hole in the Hill Country, has remained open. Baker says smaller springs have helped keep Cypress Creek flowing, but the creek is being tested weekly to ensure bacteria levels don’t get too high as water has been flowing slower than usual.

“As these flows diminish, it threatens aquatic life,” he said. “There are huge sections of the creek that are completely bone dry. No water at all.”

The Wimberley Water Supply Corporation says water levels within the Middle Trinity Aquifer — which supplies Jacob's Well — are dropping at an alarming rate due to high temperatures, population increase, lack of rainfall, tourism and development.

The City of Wimberley has tips to start water conservation efforts indoors, outdoors and in commercial facilities on their website.

Published August 2, 2023 (Source)

Jacob's Well, the popular spring-fed swimming hole in Wimberley, has reached zero flow for the sixth time in its recorded history. All six of those times have occurred in the last 23 years — and it's become more frequent.

Earlier this summer, the Hays County park announced Jacob's Well had low flow and would likely not open for swimming. Now, its flow has stopped entirely.

David Baker, executive director of the nonprofit The Watershed Association, has worked to protect the well and the surrounding natural environment for almost 30 years. He said this is the worst he’s ever seen it.

“It's heartbreaking,” he said. “We've worked so hard. The community has invested lots of money in buying up land to protect it.”

Low water levels at Jacob’s Well have been a recurring issue, and experts say the well’s health is an indicator of the region’s water supply. Baker says more water is taken out of the aquifers each year and not enough is going back in to recharge them.

“There’s no water flowing out of the creek at all,” Baker said. “We're still in a very severe extreme drought here in Central Texas. You look at the drought monitor and you'll see that big, dark brown circle there in the middle of Texas.”

The City of Wimberley entered Stage 4 drought conditions on Tuesday. The Hays Trinity Groundwater Conservation District will need to decrease its water use district-wide by 40% — and by 30% within the Jacob’s Well Groundwater Management Zone. The district says both the Pedernales and Blanco rivers are experiencing record-low flows.

“It's really an ecological disaster, it's an economic disaster,” Baker said. “The county has lost hundreds of thousands of dollars in revenue from not being able to allow swimmers there for the past two summers.”

Blue Hole Regional Park, another nearby swimming hole in the Hill Country, has remained open. Baker says smaller springs have helped keep Cypress Creek flowing, but the creek is being tested weekly to ensure bacteria levels don’t get too high as water has been flowing slower than usual.

“As these flows diminish, it threatens aquatic life,” he said. “There are huge sections of the creek that are completely bone dry. No water at all.”

The Wimberley Water Supply Corporation says water levels within the Middle Trinity Aquifer — which supplies Jacob's Well — are dropping at an alarming rate due to high temperatures, population increase, lack of rainfall, tourism and development.

The City of Wimberley has tips to start water conservation efforts indoors, outdoors and in commercial facilities on their website.

WE NEED RAIN NOW!!!

August 2022

|

As our 2022 seasons transitioned from late winter to spring, our surrounding yard areas required early season attention. After these early touchups, it became evident our well-worn mower was ready for replacement. In early May we assumed periodic rains would produce the need for mowing. Some investigation indicated we might choose to move to battery powered heavy-duty equipment this time. An order was placed, replacement arrived and it still remains “ready and waiting.” Our expectations for rainfall have been left wanting, becoming desperate as the weeks come and go. It is as if from then until now a rare dark cloud passes our way overhead and finds our readiness and waiting mockingly laughable. We have even heard thunder a time or two. But, alas, it is anything but a joke! The drought deepens weekly and the stressors abound.

In this week of writing, Jacob’s well in Wimberly has gone dry for only the fourth time ever. This caps a series of reports from friends, family and correspondents about worrisome images across our Texas Hill Country. Images of riverbeds gone dry and looking more like an empty roadway bed; little pools of water with desperate fish, some the threatened Guadalupe bass; stories of stranded docks and boat launchings. Others have called attention to the frailty of wildlife and the super crowded influx of livestock going to auction. We have even had a nearby wildfire scare that left scorched acreage as a caution. My most haunting image comes from my marvelous wife of 59 years and friend for 66 describing a 1950’s trip with younger siblings on the train from the verdant green stretches of the Midwest through a long stretch of Texas where her Comal County grandparents and aunt met them at the downtown New Braunfels depot. She said the deeper they came into Texas, the drier the landscape with |

occasional frightful sightings of emaciated cattle. Peering from the train windows or landings where you could look out between coaches back then, the savaging of Texas by deep drought cried out! Today along with the images of wildfires even nearby gives one shivers.

The ominous signs of these periodic droughts, especially noting records that show the recent recordings of severe precipitation deprivation clustering in our recent decades gives one pause. I know there are those insistent that we cannot have conversation using “global warming” or “climate change” without creating division. So, let’s just allow the circumstances to shake us into some reality thinking and reflection. It would seem a “no brainer” that those among us in Comal County and neighbors of the Texas Hill Country working to protect and set aside “green” acres in conservation protection are about a good thing. As the aquifers strain to provide, such efforts above recharge areas seem urgent. Likewise, isn’t it a considerable shortsightedness to have “stages for conservation” with our water supplies as these stressful periods are notably more frequent? It is high time for policy revisions. In a state so dependent upon underground water resources, the time has come for policy that establishes scientific oversight as well. A recent revisit of my TEXAS WATER ATLAS proved instructive. An update in projections of population growth bringing water “takes” at more rapid rates is needed to note the exponential growth in our Texas Hill Country and “along the corridor.” Our withering summer sounds the alarms. Yes, friends, conserve, landscape in drought hardy ways and make provision to capture rainwaters. The time to “do water” responsibly is now! Resources are readily accessible at www.comalconservation.org and our excellent local libraries. |

Drought drama: With Edwards Aquifer low and waterways drying up, more restrictions could be coming

By Elena Bruess

April 10, 2023

April 10, 2023

By the time the area's drought reached its third year, the creeks and rivers of South Central Texas had long dried up. For most, it happened slowly, shrinking over time until just a puddle remained. For others, it was a shock. One summer, there was water. The next, there was none. Either way, the waterways that normally flowed through the Hill Country had dried into the rock beds and the time for swimming was over.

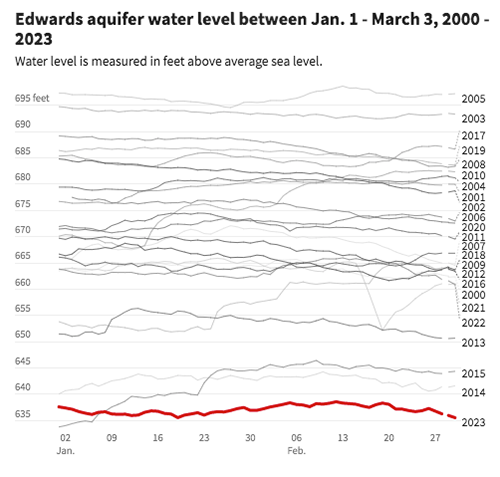

The ongoing drought's repercussions are clear in the San Antonio area. River and creek flows are at the slowest they have ever been, lakes are dried up or are drying up and, from January to March this year, the Edwards Aquifer's water levels reached their lowest levels since the record drought of the 1950s. Without normal rainfall, the agency that manages the aquifer could find itself implementing Stage 4 restrictions earlier this year than any time in its history.

The ongoing drought's repercussions are clear in the San Antonio area. River and creek flows are at the slowest they have ever been, lakes are dried up or are drying up and, from January to March this year, the Edwards Aquifer's water levels reached their lowest levels since the record drought of the 1950s. Without normal rainfall, the agency that manages the aquifer could find itself implementing Stage 4 restrictions earlier this year than any time in its history.

Over 2 million people, including thousands of farmers, depend on water from the Edwards Aquifer, a porous limestone cavern system spanning hundreds of feet underground and across 3,600 square miles. The aquifer provides the San Antonio Water System with just over 50 percent of its water supply.

The aquifer’s current water level is at 635 feet, having dropped more than 15 feet in the past year and about 2 feet in the past 10 days. When the rolling average drops below 630 feet, it will trigger the Edwards Aquifer Authority — the government entity that regulates use of the aquifer — to call for Stage 4 water restrictions for suppliers who draw from the aquifer. Those restrictions mean reducing pumping by 40 percent from normal levels — a major cutback for some Hill Country communities, many of whom get all their water from the aquifer.

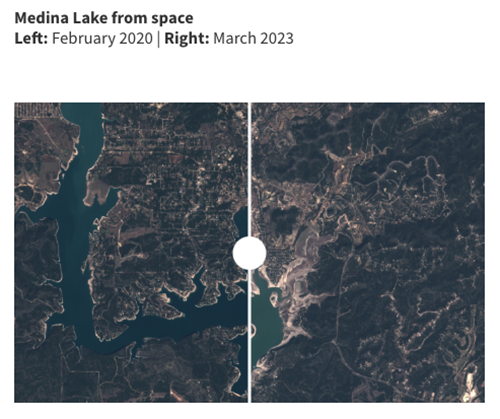

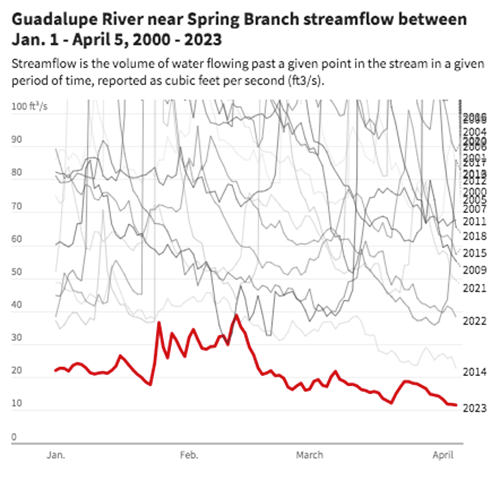

At the same time, surface water throughout South Central Texas is being sucked dry. The Guadalupe, Medina and Llano rivers have had historically low flows for this time of the year, while Canyon and Medina lakes are shrinking. And a number of popular natural swimming holes, such as Jacob’s Well in Wimberley, are shut down.

The aquifer’s current water level is at 635 feet, having dropped more than 15 feet in the past year and about 2 feet in the past 10 days. When the rolling average drops below 630 feet, it will trigger the Edwards Aquifer Authority — the government entity that regulates use of the aquifer — to call for Stage 4 water restrictions for suppliers who draw from the aquifer. Those restrictions mean reducing pumping by 40 percent from normal levels — a major cutback for some Hill Country communities, many of whom get all their water from the aquifer.

At the same time, surface water throughout South Central Texas is being sucked dry. The Guadalupe, Medina and Llano rivers have had historically low flows for this time of the year, while Canyon and Medina lakes are shrinking. And a number of popular natural swimming holes, such as Jacob’s Well in Wimberley, are shut down.

Paul Bertetti, the Edwards Aquifer Authority's senior director of aquifer science research and modeling, says this means the next few weeks are vital for the drought.

“It’s all about rainfall,” he said. “Even if we have normal rainfall during May and June’s rainy months, we should expect to see the same declines as we would during the summer. Unfortunately, at this point we have not even received a normal amount of rainfall. We’re about half of normal.”

Between January and March this year, the San Antonio area received 3.17 inches of rain. The average at this point of the year is 6 inches.

“If we follow this trend, we could see Stage 4 restrictions by early this summer,” Bertetti said. “If that’s the case, some communities will potentially be under a lot more stress this year.”

“It’s all about rainfall,” he said. “Even if we have normal rainfall during May and June’s rainy months, we should expect to see the same declines as we would during the summer. Unfortunately, at this point we have not even received a normal amount of rainfall. We’re about half of normal.”

Between January and March this year, the San Antonio area received 3.17 inches of rain. The average at this point of the year is 6 inches.

“If we follow this trend, we could see Stage 4 restrictions by early this summer,” Bertetti said. “If that’s the case, some communities will potentially be under a lot more stress this year.”

LAWATER RESTRICTIONS COULD GET TIGHTER

Since the Edwards Aquifer Authority created initial drought rules in 2000, restrictions have reached Stage 4 only twice, in 2014 and 2022.

Because of drought from 2011 to 2014, the authority implemented 89 days of Stage 4 restrictions -- which requires a 40 percent reduction of aquifer use -- from August to November. In 2022, after a year of severe drought, the area entered Stage 4 in August for a few days and again in October for a total of 24 days.

While there is always significant uncertainty, projections by the Edwards Aquifer Authority found that at normal rainfall, the aquifer could reach Stage 4 in August. But with less than normal rainfall, it could be as early as June.

However, San Antonio’s city-owned water utility, the San Antonio Water System, has its own set of regulations. Because SAWS also gets water from sources other than the Edwards Aquifer, the utility has gone only into Stage 2 watering restrictions during this drought. Stage 2 restrictions mean SAWS customers are limited to watering their lawns once per week.

Even if the Edwards Aquifer Authority enters Stage 4, it's not a guarantee that SAWS would also tighten its restrictions and move to Stage 3, which would limit watering to every other week. SAWS says it will analyze water supplies and customer demand every two weeks.

“The way the city ordinance is crafted is that Stage 3 is something that we start contemplating once the Edwards Aquifer triggers Stage 3, and if it appears that we’re not going to have enough apply to meet demand going forward, SAWS would recommend with the city manager to go into Stage 3,” said Karen Guz, vice president of water conservation at SAWS.

“The answer at the moment is no, not right now. We are not recommending" Stage 3.

Recently, the utility has been cracking down on water use violators. From Jan. 1 to last Wednesday, SAWS issued 1,136 citations and 734 warnings to residents for not following watering restrictions. A citation costs about $130.

On average, depending on family size, a home might use 5,000 gallons a month in winter and 8,000 gallons a month in summer. Houses with an automatic irrigation system might use as much as 15,000 gallons a month.

But when SAWS officials see a customer using 20,000 gallons or more, they know something is wrong. That is more water than 95 percent of the other SAWS customers.

“It would be premature to move to Stage 3 before we ramp up enforcement on Stage 2 through community messaging and communications,” Guz said. “We are watching the Edwards Aquifer constantly.”

On the other hand, communities outside of San Antonio might need to jump when the Edwards Aquifer Authority says jump.

Alamo Heights depends entirely on the Edwards Aquifer for water. Currently, the city is in Stage 3 watering restrictions, meaning watering once every other week. If the region enters Stage 4, the Alamo Heights City Council might hold an emergency session to consider other watering restrictions.

If the City Council "wants to incorporate more stringent conservation measures or whatever it may be, they can," said Patrick Sullivan, public works director for Alamo Heights. "But they'll be the ones to determine if we need to make any adjustments."

New Braunfels anticipates pulling about 6,000 acre-feet in total from the Edwards Aquifer this year. In the case of Stage 4, New Braunfels Utilities would determine if stricter measures were necessary, according to the city. Watering restrictions, landscape limitations and other activities would be examined on a day-to-day basis until Stage 4 could be lifted.

LAKES, WATERWAYS DRYING UP

Since the Edwards Aquifer Authority created initial drought rules in 2000, restrictions have reached Stage 4 only twice, in 2014 and 2022.

Because of drought from 2011 to 2014, the authority implemented 89 days of Stage 4 restrictions -- which requires a 40 percent reduction of aquifer use -- from August to November. In 2022, after a year of severe drought, the area entered Stage 4 in August for a few days and again in October for a total of 24 days.

While there is always significant uncertainty, projections by the Edwards Aquifer Authority found that at normal rainfall, the aquifer could reach Stage 4 in August. But with less than normal rainfall, it could be as early as June.

However, San Antonio’s city-owned water utility, the San Antonio Water System, has its own set of regulations. Because SAWS also gets water from sources other than the Edwards Aquifer, the utility has gone only into Stage 2 watering restrictions during this drought. Stage 2 restrictions mean SAWS customers are limited to watering their lawns once per week.

Even if the Edwards Aquifer Authority enters Stage 4, it's not a guarantee that SAWS would also tighten its restrictions and move to Stage 3, which would limit watering to every other week. SAWS says it will analyze water supplies and customer demand every two weeks.

“The way the city ordinance is crafted is that Stage 3 is something that we start contemplating once the Edwards Aquifer triggers Stage 3, and if it appears that we’re not going to have enough apply to meet demand going forward, SAWS would recommend with the city manager to go into Stage 3,” said Karen Guz, vice president of water conservation at SAWS.

“The answer at the moment is no, not right now. We are not recommending" Stage 3.

Recently, the utility has been cracking down on water use violators. From Jan. 1 to last Wednesday, SAWS issued 1,136 citations and 734 warnings to residents for not following watering restrictions. A citation costs about $130.

On average, depending on family size, a home might use 5,000 gallons a month in winter and 8,000 gallons a month in summer. Houses with an automatic irrigation system might use as much as 15,000 gallons a month.

But when SAWS officials see a customer using 20,000 gallons or more, they know something is wrong. That is more water than 95 percent of the other SAWS customers.

“It would be premature to move to Stage 3 before we ramp up enforcement on Stage 2 through community messaging and communications,” Guz said. “We are watching the Edwards Aquifer constantly.”

On the other hand, communities outside of San Antonio might need to jump when the Edwards Aquifer Authority says jump.

Alamo Heights depends entirely on the Edwards Aquifer for water. Currently, the city is in Stage 3 watering restrictions, meaning watering once every other week. If the region enters Stage 4, the Alamo Heights City Council might hold an emergency session to consider other watering restrictions.

If the City Council "wants to incorporate more stringent conservation measures or whatever it may be, they can," said Patrick Sullivan, public works director for Alamo Heights. "But they'll be the ones to determine if we need to make any adjustments."

New Braunfels anticipates pulling about 6,000 acre-feet in total from the Edwards Aquifer this year. In the case of Stage 4, New Braunfels Utilities would determine if stricter measures were necessary, according to the city. Watering restrictions, landscape limitations and other activities would be examined on a day-to-day basis until Stage 4 could be lifted.

LAKES, WATERWAYS DRYING UP

A car crosses the dry Guadalupe River at the Rebecca Creek Road crossing Jan. 25, 2023, as the river upstream from Canyon Lake remains abnormally low. Despite rains earlier in the week, the river remains far below its median flow rate in this area for this time of year of about 150 cubic feet per second and goes completely dry before reaching Canyon Lake. Prior to the rains, the USGS gauge just upstream from Rebecca Creek Road at FM 311 had been showing a flow rate of about 18 cfs in the river. The rains brought the flow up to 43 cfs for a few hours before the river began dropping again. — William Luther/Staff

For nearly two years, the United States has been under the influence of La Niña, a global climate pattern that causes an increase in drought and heat throughout the South. The weather has since shifted, however, and neutrality has taken over.

Neutral means normal patterns, such as more typical heat and rainfall through the spring and summer. This would be better for San Antonio’s drought, but not good enough. El Niño, a weather pattern that brings rain and colder than average temperatures to the southern U.S., could increase the amount of precipitation, said Bertetti of the Edwards Aquifer Authority. However, climatologists don’t foresee El Niño activities until fall.

Last year, San Antonio was 20 inches below normal precipitation – meaning it will take a lot of water to bounce back from the drought and the Edwards Aquifer region should expect drought restrictions for the entire year. It also means the rivers, creeks and lakes will continue to struggle.

Neutral means normal patterns, such as more typical heat and rainfall through the spring and summer. This would be better for San Antonio’s drought, but not good enough. El Niño, a weather pattern that brings rain and colder than average temperatures to the southern U.S., could increase the amount of precipitation, said Bertetti of the Edwards Aquifer Authority. However, climatologists don’t foresee El Niño activities until fall.

Last year, San Antonio was 20 inches below normal precipitation – meaning it will take a lot of water to bounce back from the drought and the Edwards Aquifer region should expect drought restrictions for the entire year. It also means the rivers, creeks and lakes will continue to struggle.

Of the 306 creek and river gauging stations in the San Antonio area, 34 percent are below normal and 22 percent are well below normal as of March, said Doug Schnoebelen, branch chief for the South Texas U.S. Geological Survey. Both the Guadalupe River Basin and the San Antonio River Basin are of concern.

Adequate flows in rivers, creeks and lakes are crucial for wildlife that depend on the aquatic ecosystem, according to experts. Without enough water, fish will compete for oxygen as the water levels shrink and harmful algae blooms and bacteria growth can form in stagnant areas. Some aquatic species can adapt to low flow and move to areas with higher flow, but other species, such as mussels, are too slow to move and will die out. Animals will generally be able to bounce back after the flows increase again, but in the case of an incredibly low flow event, some species may be in more trouble.

Low water flow also affects local economies and businesses. Tubing operations could go out of business for an entire summer, or local lakeside restaurants could see a decrease in customers. In the Medina Lake community, lake view property taxes are the same even without a lake and Realtors are selling on the prospect of future water.

Adequate flows in rivers, creeks and lakes are crucial for wildlife that depend on the aquatic ecosystem, according to experts. Without enough water, fish will compete for oxygen as the water levels shrink and harmful algae blooms and bacteria growth can form in stagnant areas. Some aquatic species can adapt to low flow and move to areas with higher flow, but other species, such as mussels, are too slow to move and will die out. Animals will generally be able to bounce back after the flows increase again, but in the case of an incredibly low flow event, some species may be in more trouble.

Low water flow also affects local economies and businesses. Tubing operations could go out of business for an entire summer, or local lakeside restaurants could see a decrease in customers. In the Medina Lake community, lake view property taxes are the same even without a lake and Realtors are selling on the prospect of future water.

“If we don't get rain this spring, it will be a missed opportunity for these creeks and rivers,” Schnoebelen said. “And going into the summer usually doesn’t look good because of the high heat, high humidity and high evaporation rates. It takes a lot of rain to recharge these streams and then to recharge the aquifer.”

Based on 40 years of data, the Medina River in Bandera is at its lowest flows in history. The average water flow is 139 cubic feet per second. As of last Wednesday, the flow is 5.81 cubic feet per second. Based on 32 years of recorded data, the Guadalupe River just north of San Antonio is at 1.63 cubic feet per second, which is the lowest it has ever been. Prior to this year, the record low was 1.73 cubic feet per second in 2014. A cubic foot of water is about the size of a basketball.

“That’s the thing about Texas is we have really high water flows and then really low water flows,” Schnoebelen said. “Right now, we’re in a drought. Next year, we could be flooding.”

The last time creek and river levels were this low was in 2014, during the years-long drought in South Central Texas. Still, last year’s lack of precipitation beat out that year and every year since 1917. Medina Lake, a reservoir about 50 miles west of San Antonio, is at 5.3 percent of capacity. It dropped about 16 percent in a year because of irrigation pumping and the drought. The last time the levels were that low was in 2015.

Canyon Lake, a reservoir north of San Antonio, is at 76.3 percent capacity, having dropped 20 percent in the past year. If the lake drops an additional 5 feet, it will reach its lowest levels in the past 50 years.

“This rain we’ve gotten recently is maybe enough to keep the grass green, but it’s really not enough for our streams or our reservoirs or our aquifer,” Schnoebelen said. “That’s what we need.

Based on 40 years of data, the Medina River in Bandera is at its lowest flows in history. The average water flow is 139 cubic feet per second. As of last Wednesday, the flow is 5.81 cubic feet per second. Based on 32 years of recorded data, the Guadalupe River just north of San Antonio is at 1.63 cubic feet per second, which is the lowest it has ever been. Prior to this year, the record low was 1.73 cubic feet per second in 2014. A cubic foot of water is about the size of a basketball.

“That’s the thing about Texas is we have really high water flows and then really low water flows,” Schnoebelen said. “Right now, we’re in a drought. Next year, we could be flooding.”

The last time creek and river levels were this low was in 2014, during the years-long drought in South Central Texas. Still, last year’s lack of precipitation beat out that year and every year since 1917. Medina Lake, a reservoir about 50 miles west of San Antonio, is at 5.3 percent of capacity. It dropped about 16 percent in a year because of irrigation pumping and the drought. The last time the levels were that low was in 2015.

Canyon Lake, a reservoir north of San Antonio, is at 76.3 percent capacity, having dropped 20 percent in the past year. If the lake drops an additional 5 feet, it will reach its lowest levels in the past 50 years.

“This rain we’ve gotten recently is maybe enough to keep the grass green, but it’s really not enough for our streams or our reservoirs or our aquifer,” Schnoebelen said. “That’s what we need.

Recording: How the ongoing drought impacts the Hill Country

On February 22nd, Schreiner University, Hill Country Alliance, and Texas Public Radio hosted the 2023 Texas Water Symposium. The panel was focused on how the ongoing drought impacts the Hill Country, and included Tara Bushnoe, General Manager of the Upper Guadalupe River Authority, Dave Mauk, General Manager of the Bandera County River Authority and Groundwater District, Benedicte Rhyne of Wine Country Consulting, and Bob Barker of C&M Precast. You can listen to a live recording of the panel here.

Members of the Balch Springs Fire Department bring a family of four by boat to higher ground after rescuing them from their home on Forest Glen Lane in Balch Springs, Texas on August 22, 2022. Amid severe drought in much of Texas, recent weeks have also seen damaging rains in parts of the state. Elîas Valverde II, The Dallas Morning News/AP

Heat. Drought. Fires. Floods. Texas grapples with a new era.

By Henry Gass, Xander Peters

August 31, 202

August 31, 202

|

ZAPATA, SMITHVILLE, AND GALVESTON, TEXAS

When engineer Manuel Gonzalez moved back to his hometown of Zapata 20 years ago, the Texas community was in a major local drought. “It was their challenge [then]. It’s my challenge now,” he says. Standing by the reservoir that serves as the town’s only water source, he shows the modest solution he’s been helping to build: |

A small structure of mud and rock, stretching a few feet into the Rio Grande-fed Falcon Lake Reservoir. At its edge he can pick up cellphone service from Mexico. More important, from it county pumps can access 15 feet of water – compared to 3 feet near the shoreline.

His effort is part of a transformation underway in a state that is feeling effects of climate change like never before |

WHY WE WROTE THIS

While climate change has not been a top political concern in Texas, it is increasingly emblematic of America’s climate change experience. From heat to damaging rains, this summer looks like a pivot point.

While climate change has not been a top political concern in Texas, it is increasingly emblematic of America’s climate change experience. From heat to damaging rains, this summer looks like a pivot point.

|

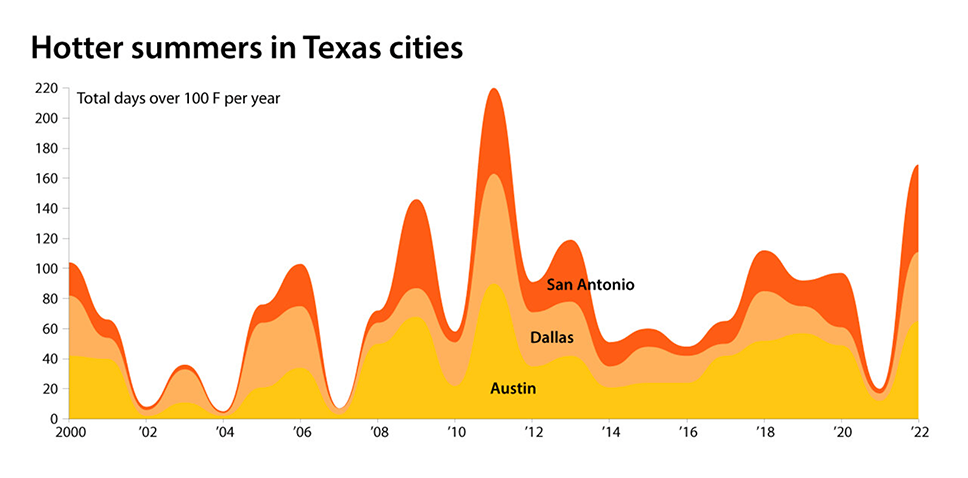

Almost every corner of the state has been experiencing extreme heat, and, until recently, often no rain too. These patterns of heat and drought aren’t limited to Texas, but the trends here are noteworthy. The Lone Star State, after all, ranks second only to California in population and is among the fastest growing states. It’s a linchpin of the U.S. economy, from energy to tech. And as a solidly Republican red state, it’s a place where evolving views toward climate could have outsize political effects. Already attitudes have been shifting. The share of Texans who believe climate change is currently harming people in the United States has risen from 50% in 2018 (slightly below the |

national average in that year) to 60% last year (just above the national average), according to Yale Climate Opinion Maps. This summer may be a preview of what scientists say could become normal conditions for the state. By 2036, Texas’ bicentennial year, there will be nearly twice as many 100-degree days as there are today, according to a study last year by Texas A&M University and Texas 2036, a nonprofit, nonpartisan policy organization in the state. Droughts are expected to become more severe, as are extreme rainfall events. Meanwhile, population growth is projected to accelerate.States has risen from 50% in 2018 (slightly below the national average in that year) to 60% last year (just above the national average), according to Yale Climate Opinion Maps. |

|

But in the face of these challenges, Texans have been demonstrating resiliency and innovation. From connecting local water services, to adapting the state’s water plan, to cooperating with a nationwide wildfire response network, the state is working to adapt to, and prepare for, a climate change-altered future.

RESPONDING TO SEVERE DROUGHT For almost a year, almost all of Texas has been in drought conditions, much of it extreme. In mid-August, 99% of the state was experiencing “abnormally dry” conditions, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor, with over 97% experiencing the two most severe categories of drought. If the drought persists, experts say it may rival 2011, the worst single-year drought recorded in state history. In Zapata, the community of 14,000 has been caught between the Texas drought and a decadeslong drought in northern Mexico. Now the old Highway 83 is visible, 70 years after it was submerged by the Falcon Lake Reservoir. Javier Santiago (left) and Manuel Gonzalez survey the Falcon Lake Reservoir near the old Highway 83. The highway is normally underwater, but extreme drought this year has revealed the bridge, and threatened the community's only source of water.The structure Mr. Gonzalez helped build is just one solution. The community has also interconnected four local water providers so they can share resources. In early August, they announced an agreement between U.S. and Mexican officials to dredge sections of the reservoir and increase water depth. And Mr. Gonzalez, who runs a private engineering firm in south Texas, has been commissioned by the county to study potential secondary sources of water, including reusing wastewater. “We’re not there yet, but we are starting to look.” That seems to be the trend. The 2011 drought was thought to be the kind you get twice a century. “We’re having a drought [now] that looks very similar a mere 10 years after that 2011 drought,” says Robert Mace, a professor at |

Texas State University and executive director of the Meadows Center for Water and the Environment, in an interview earlier this month.

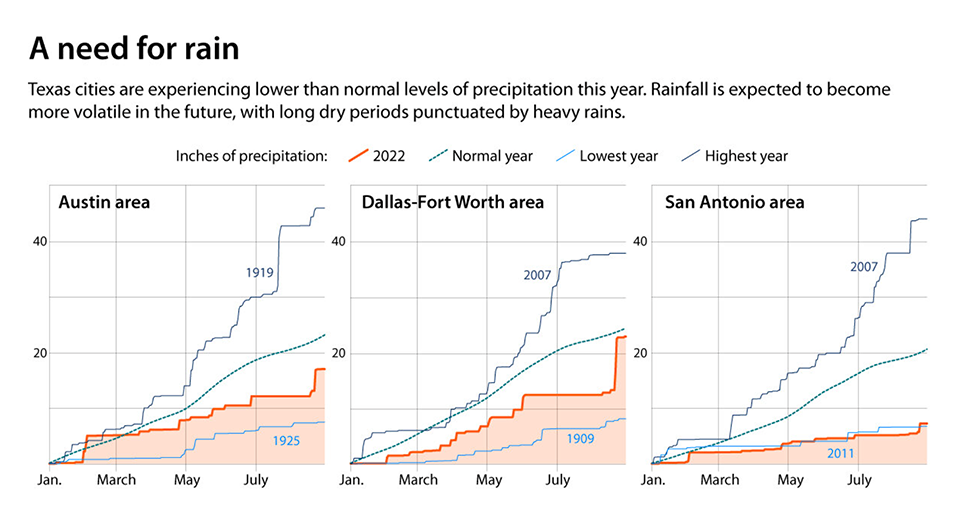

“We’ll be seeing drought conditions become a new normal for the state.” TRIPLE-DIGIT TEMERATURES ON THE RISE Heat and drought go hand in hand. As surface temperature increases, so does evaporation, and soil and foliage struggle to retain moisture. The extreme heat this summer has been especially keen in Texas’ major cities. Both Austin and San Antonio had their hottest May on record, followed by their hottest June on record, followed by their hottest July on record. Simultaneously, there has been very little rain. San Antonio is experiencing its worst year on record for rainfall. The Austin and Dallas areas went 52 and 67 days, respectively, without rain between June and August. This is partly due to an ongoing climate pattern known as La Niña. This cyclical pattern sees cooler than normal surface temperatures in the equatorial Pacific Ocean push rainfall and cooler temperatures away from the southern U.S. While this La Niña has been relatively mild, according to Dr. Mace, it has also been long – projected to last for a rare third consecutive winter. It’s unclear how climate change will affect La Niña, but it’s “very likely” that rainfall variability will significantly increase in the latter half of this century, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s 2021 report. This summer Texas has had a preview of what that could look like. A few weeks after snapping its 67-day rainless streak, Dallas experienced what’s been called a “one-in-a-thousand-year” flooding event. Over 9 inches of rain fell in 24 hours – more rain than the area typically sees in a whole summer – and caused as much as $6 billion in damages, according to an estimate from AccuWeather. |

|

The Texas 2036 report on future climate changes in the state “not only pointed to increased future drought severity, but paradoxically a likely increase in future flood events,” says Jeremy Mazur, senior policy adviser on natural resources at Texas 2036.

The state’s surface temperature is predicted to be 3 degrees hotter by 2036, he adds. “What we’ll [then be] seeing is stronger peaks and longer valleys with regards to rainfall.” |

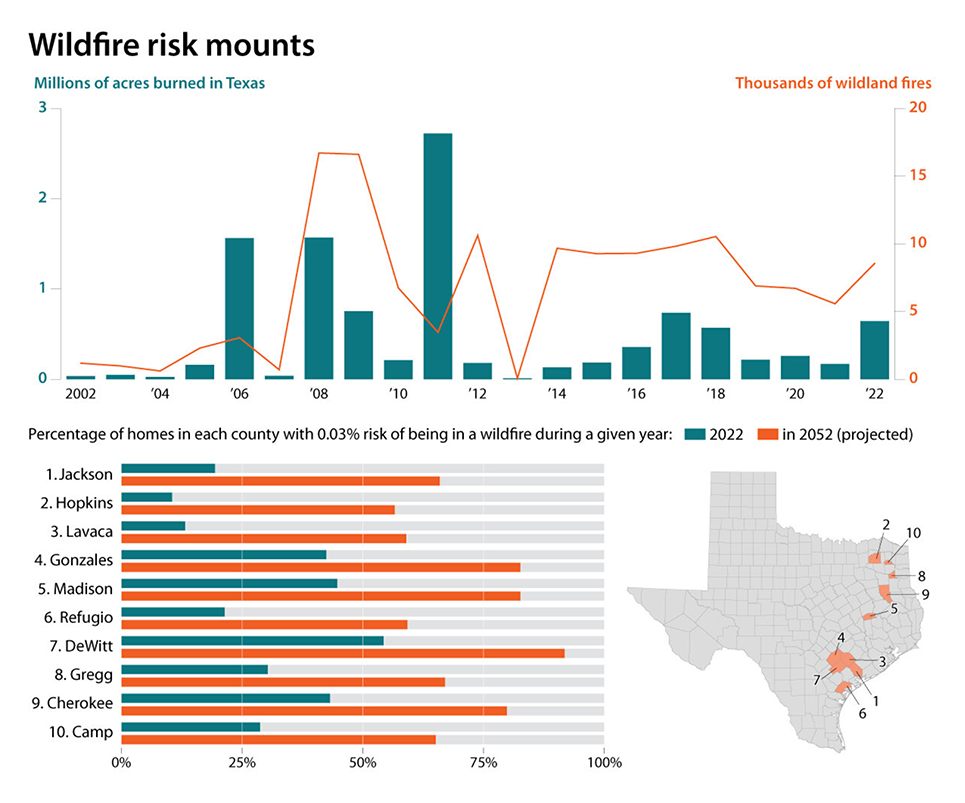

WILDFIRES GET HARDER TO CONTAIN

One area where Texas – and the country – has shown great resilience and resourcefulness is in combating the growing threat of wildfire. No two fire seasons are the same, but this year’s has been the busiest for Texas since 2011, with over 8,800 wildfires burning over 630,000 acres across the state. And risks are projected to grow as the state becomes hotter and more populated. Assistance from thousands of firefighters from around the state and country, coordinated through a national interagency network, has helped minimize the recent damage |

Jimmy McDonald (from left), John Jopling, and Tim Shillern of the Nacogdoches Fire Department extinguish a smoldering log while working on the Pine Pond Fire. Effective coordination between agencies inside and outside Texas has helped limit damage from wildland fires during one of the driest years on record in the state. Henry Gass/The Christian Science Monitor

|

Earlier this month, 56 of those firefighters gathered near Smithville, an hour west of Austin, to prepare for another day fighting the 700-acre Pine Pond Fire.

The previous day brought the county’s first significant rain in 52 days, but because it has been so dry, firefighters spend the morning patrolling fire lines for hazards that could reignite. They drive or walk over the charred landscape looking for “snags” – dead, standing trees that could be smoldering on the inside – and sniffing the air for “new” smoke (more pungent than “old” smoke). |

Around noon, as the sun begins to pierce the clouds, four men from the Nacogdoches Fire Department hack their way toward a smoking log deep inside a section of unburned trees, surrounded by dry pine needles and leaves. It’s this kind of hazard they’ve been extinguishing all morning.

The men primarily fight structure fires, but in a normal year they go on one to three wildland fire deployments. This year they’ve had one or two deployments each month. They make short work of the log – scraping off the ash and dousing it in water – and head back out to look for the next problem |

|

Wildfires “are becoming more problematic to try to keep within the [containment] line,” says Steve Willingham, a resource specialist with the Texas A&M Forest Service and the senior incident commander for the Pine Pond Fire.

Yet wildfire response shows that statewide resources – nationwide resources, even – can be harnessed effectively when there’s a will to do so. “It keeps guys alive,” says Mr. Willingham. “It keeps people safe.” FLOODWATERS AND NEW DEFENSES The hope for rain varies by region in Texas. Travel east from dry Central Texas to the Gulf Coast’s emerald-green waters and |

it’s the persistent threat of flooding that grips researchers attempting to better understand the region’s future.

In August 2017, Hurricane Harvey dumped trillions of gallons of rainfall across metropolitan Houston and rural southeast Texas. The storm amounted to the second-costliest natural disaster in U.S. history, with $125 billion in damages – and a 2020 study in the journal Climate Change estimated that at least $30 billion of that was “attributable to the human influence on climate.” It’s not just changes in the atmosphere that make climate change costly. It’s also the built environment, says Samuel Brody, a professor at Texas A&M University at Galveston and the director of the Institute for a Disaster Resilient Texas |

|

Focusing on the forces of nature, he says, “misses the whole idea of parking lots and rooftops and roadways and all this runoff we’re creating in downstream communities.”

In response, the institute recently launched a state-funded two-year project called Digital Risk Infrastructure Program, or DRIP. It partners with underserved Texas communities to solve flooding problems through data and analytical techniques. The upshot: Communities like tiny Premont (an early DRIP partner, population 2,500) tell their flood stories, which inform the project’s solutions for mitigating future risks. Among the state’s needs is defending against rising seas as well as heavier rains. Most ambitious among Texas climate-adaptation proposals is the proposed Dutch-inspired “Ike Dike,” named after the devastating 2008 hurricane that wiped out |

roughly 60% of structures on nearby Bolivar Peninsula and threatened Houston-area transportation routes. It was recently approved by Congress but funding remains to be approved.

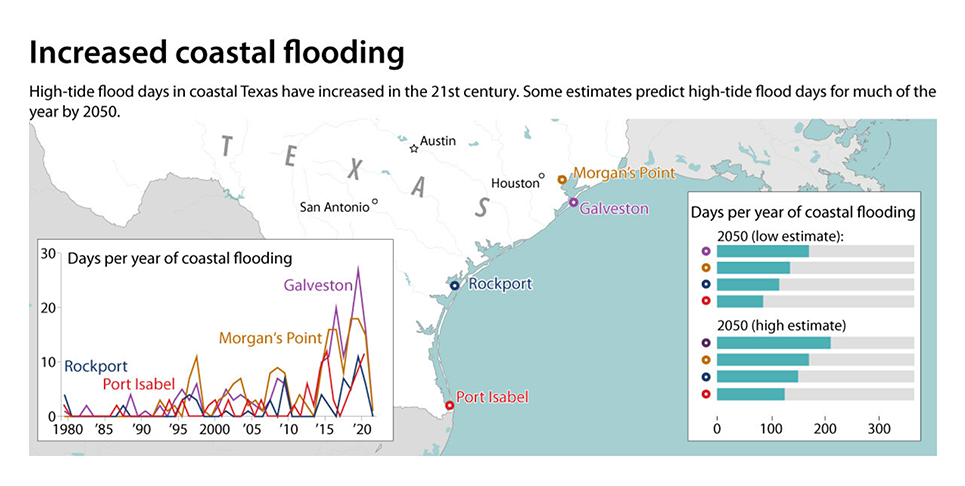

Even if the dike system is built, big risks would remain. Galveston Island, for example, is gradually sinking even as sea levels also rise. Twenty years ago, Galveston witnessed roughly three annual high-tide flood days; last year, there were 14. By 2050, the island is projected to experience 170 such events per year, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. “Nuisance flooding is going to start shutting down businesses,” says Bill Merrell, a marine sciences professor at Texas A&M University at Galveston, also a planner behind the Ike Dike. “If a parking lot’s occupied a third of the year with water, you’re not going to be able to function. You’ll have to adapt in some way.” |

What Does Drought Recovery Look Like?

By Robin Gary

August 2022

August 2022

|

Over the past week, Wimberley received between 1.5-2 inches of rain. It's a refreshing change to the persistent hot, dry weather this summer. Richard Shaver, Director of the Wimberley Parks and Recreation Department, asked a wise question: "What does recovery look like?" With Jacob's Well basically not flowing (see photo by David Baker above, taken 8/23/22), sections of Cypress Creek are completely dry. There is no inflow or outflow downstream at Blue Hole. Monitor wells are at record lows, and many well owners are having to rely on hauled water.

|

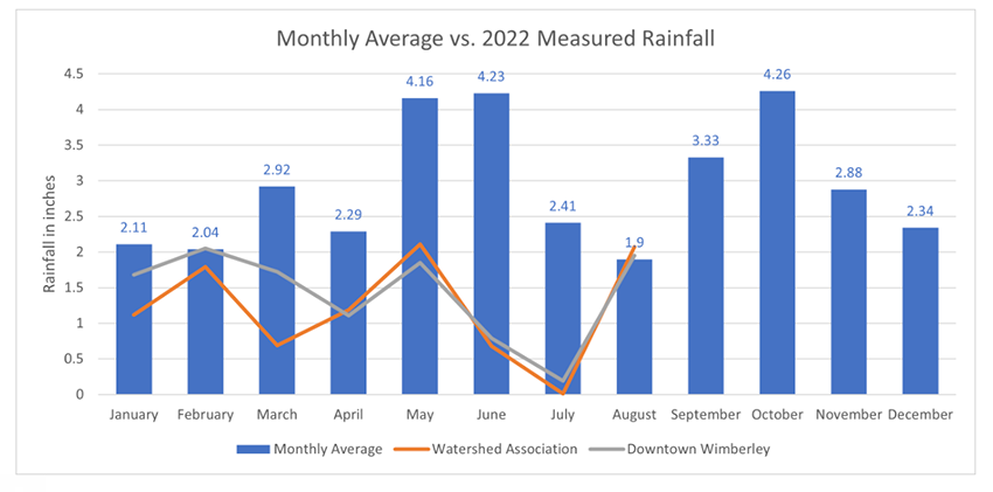

So how much rainfall would it take to return to non-drought conditions? Central Texas normally receives 33 inches a year with 22 inches coming by the end of August. As of today (August 26th), there have been 9.73 inches of rainfall at the Watershed Association office near Jacob's Well, and 11.34 inches in downtown Wimberley (Water Monitoring page). Depending on how much rain falls over the last week in August, there will still likely be a substantial rainfall deficit.

|

|

The prolonged hot and dry conditions have affected soil moisture, groundwater storage in aquifers, and flow from springs and creeks, which all have different response times to rainfall. Dry soils will likely soak up the first inch or two to the benefit of trees, grasses, and plants. After soils are saturated, they'll allow runoff to fill creeks and rivers, which funnel water into the groundwater system through karst features like caves, fractures, and sinkholes. Water levels in the Middle Trinity Aquifer in western Hays County will recover more quickly than the Lower Trinity Aquifer, which is deeper and has a confining layer that generally separates the two aquifers. Once water levels in the Middle Trinity Aquifer rise above spring elevations, spring flow will increase and supply needed baseflow to boost flow in streams like Cypress Creek and the Blanco River. Once Jacob's Well reaches a 10-day average above 6 cubic feet per second, the Hays Trinity Groundwater Conservation District will remove the drought declaration.

|

The simple answer to what drought recovery looks like is about 8-12 more inches of rain--hopefully not all at once--to get back to the average for the year. The USGS, groundwater conservation districts, and Watershed Association staff will be tracking rainfall, flow, and water levels closely to monitor drought recovery (hopefully)! There's no doubt that some rain is better than no rain! This week has been a good start on the road to drought recovery, but it will be a long road to bring groundwater storage, sustained spring flow, and creek flow back to healthy levels.

Please continue to conserve. Coordinated water conservation is key to preserve groundwater availability, spring flow, and water supplies. |

Drought as Catalyst: Hill Country Residents Seeking Greater Protections for Trinity Aquifer

By Lindsey Carnett

August 21, 2022

August 21, 2022

|

Kathleen Tobin Krueger stood on a low cliff last week, looking down on her family’s ranchland.

Below her lay an expansive field laden with smooth white rocks, trees with exposed roots growing between them. There should be a full, flowing river here — there usually is a full, flowing river here — the Medina River. Krueger stepped back from the cliff’s edge shaking her head, looking distressed. “In my whole life, I’ve never seen it like this,” Krueger said. Her family has owned the 700-acre Tobin Ranch in Bandera County for 75 years.Kathleen Tobin Krueger stood on a low cliff last week, looking down on her family’s ranchland. |

“It’s not even a mud puddle; usually it’s clear, flowing with water and lush beautiful green banks. Now it’s just white stones, laying there like bleached bones.” The former New Braunfels councilwoman and wife of the late U.S. Sen. Robert “Bob” Krueger shook her head again.

Krueger worries about the wildlife. Where are the deer and the birds getting water? She worries about their cattle. Fresh grass and clean water are getting more difficult for them to find. Krueger and the Tobin family aren’t alone in their concerns. |

|

Across Central Texas, families that depend on private wells are finding they’ve dried up — some for the first time. Ranchers are struggling to tend to water-dependent crops and to animals that can drink thousands of gallons of water a week.

While residents within San Antonio city limits who depend on the San Antonio Water System have been able to live life pretty normally this summer due to SAWS’ water diversification efforts, those living in rural areas in and around Bexar County are growing increasingly worried by the severity of the ongoing drought. Water security has long been an issue of concern for Texas, but as the state population continues to explode, droughts are becoming more intense than they have been in previous years, experts say. And while one of Central Texas’ main sources of water, the Edwards Aquifer, is protected and regulated by the Edwards Aquifer Authority, other important water sources in the region are not, or are only protected at the individual county level, despite spanning multiple counties. |

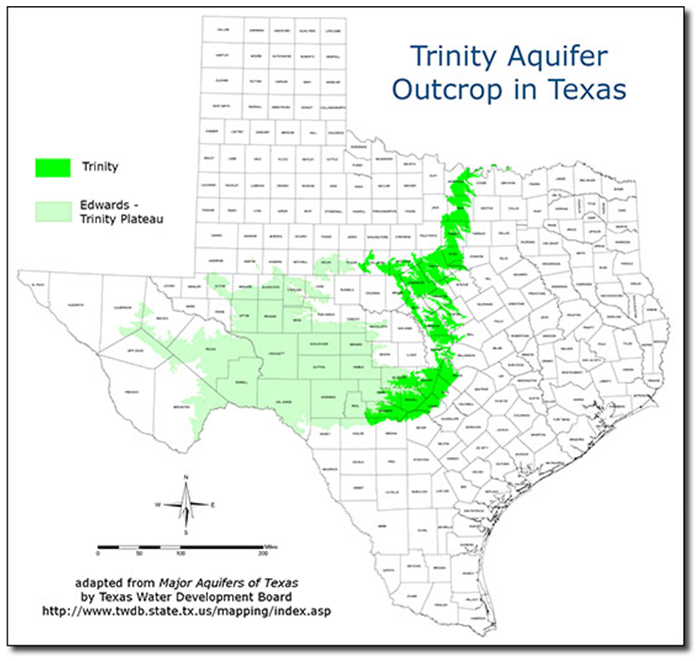

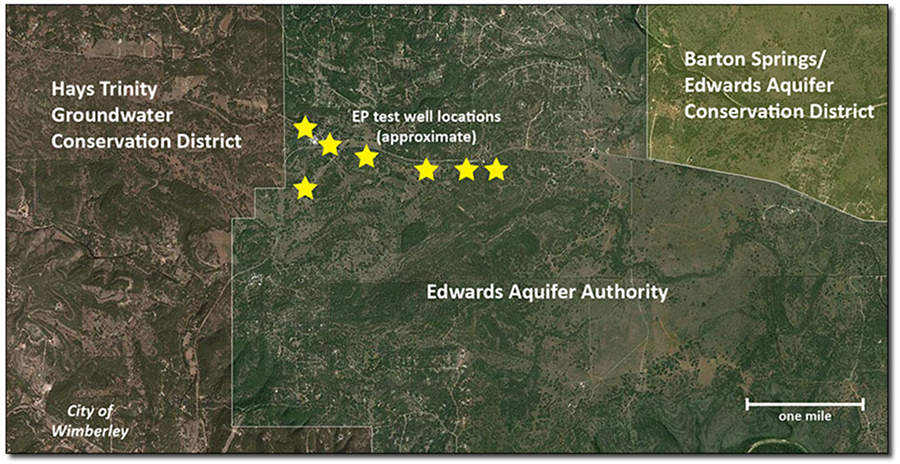

Calls to safeguard the Trinity Aquifer with similar protections that the Edwards enjoys have taken on increased urgency, as wells and tanks in the Hill Country run dry.

“[The Trinity Aquifer is] just more complicated, much more complicated, and there’s no authority for it like the Edwards Aquifer Authority that’s come through and really figured it out,” said Jack Oliver, a local geologist, cave researcher and a board member of Preserve Our Hill Country Environment. WILDLIFE ARE STRUGGLING Krueger and her brother Patrick Tobin have never been able to drive their ranch all-terrain vehicle straight up the riverbed as they can now. During a recent outing, the brother-sister pair stopped to get out and look around. As they stood on the cracked dry clay normally at the bottom of the Media River, they were dwarfed by several of the oaks and ash trees on the river’s edge. Fish bones littered the ground like confetti at some bizarre party; dozens of skulls and spines still intact lay next to each other in what must have very recently been a shallow pool of water. |

|

Another quarter mile down, buzzards lined the side of the river bank next to one such remaining pool. The small oasis was green and cloudy. Frogs flitted about everywhere along the stagnant water’s edge.

Usually, the deer, birds and fish have plenty of clean flowing water to drink and swim in the Medina River, Krueger said. She’s worried particularly for the endangered bird species that pass through their ranch annually. Krueger has good reason to be — extreme drought can be particularly difficult on Texas wildlife, said Kelly Simon, an urban wildlife biologist with the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. While much of Texas wildlife has evolved to survive drought, aspects that make modern drought particularly stressful on native Texas animals include human population growth and development, and the moving in of competitor species, such as axis deer, which compete with white tails, and red fire ants, which compete with native pollinators like bees, Simon said. “We used to say that wild types of Texas wildlife and plants are used to extremes; it’s kind of what makes Texas Texas,” Simon said. “Unfortunately, these days, it seems like the extremes are becoming normal — and so wildlife are experiencing a really difficult time.” |

THE HAY AND THE HERD

As Tobin skirted around the edge of the ranch, a nearby black cow started walking toward him and Krueger. “She probably thinks we have some food on us,” Tobin said as he passed her. The Tobins keep about 30 cattle and 25 calves on the ranch, Tobin said. Keeping them fed and watered has been an ordeal this summer, he said. The drought has caused lower hay yields than in previous years, Tobin said, making it more expensive to feed their herds. The scarcity of hay this year is also due to inflation, said Cooper Little, executive director of the Independent Cattlemen’s Association of Texas. While drought is nothing new for Texas farmers, Little said many ranchers were unable to buy good fertilizer this year due to its high cost. That resulted in less hay being grown and harvested just as the drought hit, he said. “Probably the main thing making this worse is that it was the perfect storm,” Little said. “Folks who could have hayed this year couldn’t fertilize their pastures and decided not to hay. That coincidentally fell on a year we went into drought. |

|

While Tobin Ranch has been able to produce enough water for its cattle so far, Tobin said some of their neighbors have been less lucky. He and Krueger have heard of neighbors whose stock tanks and wells have run dry, he said.

Folks across the South have been selling off their cattle because they’ve become too expensive to maintain, he said. That, in turn, has oversaturated the market. More straws in the same cupIt’s not just farmers and ranchers struggling to draw water from their wells. Residents of northern Bexar County, Comal County, and surrounding rural areas have taken to social media to talk about their private wells running dry. Oliver said Hill Country residents have been reaching out to him in recent weeks asking how they can get water trucked out to their rural homes because their wells have run dry. Oliver lives in Comal County, where for the first time since 2014 — the tail end of the last major drought — parts of the Comal Springs have gone dry. Last weekend, the Edwards Aquifer Authority declared Stage 4 pumping restrictions for its permit holders due to concern for the springs, which provide habitat for threatened and endangered species protected under the Edwards Aquifer Habitat Conservation Plan. Bryant Harris, owner of Triple H2O, a bulk potable water delivery business out of Canyon Lake, has been working 12- to 14-hour days getting water to rural customers. Harris said he’s getting calls from residents who have lived on their land for 20 years and never had their wells run this dry. While the drought of 2011 was an equally busy season for Harris, he said this year’s drought started earlier and has been marked by hotter weather — this summer has seen roughly 60 days in triple digits. What’s making this drought particularly difficult, he said, is the amount of growth the area has experienced: “There’s just so many more straws in the same cup.” |

PROTECTING THE TRINITY

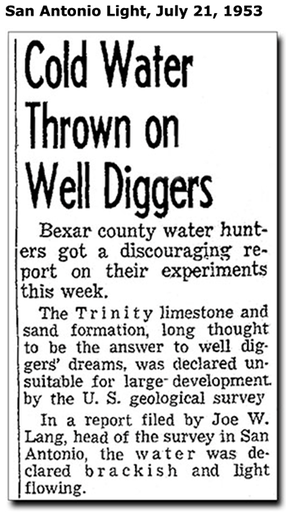

In the past, drought has acted as a catalyst in the protection of Central Texas groundwater. The creation of the Edwards Aquifer Authority can be traced to the 1950s drought of record, which didn’t end until 1957. In 1959, the Edwards Underground Water District was created to “conserve, preserve and protect” the Edwards Aquifer; however, it wasn’t given regulatory powers. In 1991, the Sierra Club filed a lawsuit against the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for failing to protect species covered by the Endangered Species Act. The lawsuit sought to require the federal agency to ensure minimum spring flows from the Edwards Aquifer to the Comal and San Marcos springs to protect endangered species living there. In 1993, a U.S. district judge ruled in favor of the Sierra Club, ordering that spring flows must be maintained. Born out of this ruling, the EAA officially launched operations in 1996. Now, environmental advocates and land owners in Central Texas are calling on state officials to add more protections to other aquifers, such as the Trinity. Preserve Our Hill Country Environment and Friends of Dry Comal Creek are seeking to get residents out in numbers to The Comal Trinity Groundwater Conservation District’s Sept. 19 board meeting to urge greater protections for the Trinity. A social media post by Preserve Our Hill Country Environment notes that drilling into the Trinity by developers and quarries is further endangering the aquifer’s security. There is definitely a need to further protect the Trinity Aquifer, Oliver said, in part because it produces at a lower rate and takes longer to recharge than the Edwards. Landowners reliant on wells that are now drying up are mostly from the Trinity rather than the Edwards. A Trinity Aquifer Authority, structured like the Edwards, would help as the region continues to grow and as climate change makes weather patterns and droughts more severe, Oliver said. |

‘The Easy Water is Gone’: Drought and Climate Change Strain Texas Aquifers

Some Texas aquifers have stopped flowing altogether, while the levels of others are drastically below normal levels.

By Jill Ament

August 1, 2022

August 1, 2022

|

With heightened concern over dwindling water supplies in communities all across Texas, many towns and cities have put in place their most strict water conservation ordinances.

Robert Mace, executive director and chief water policy expert for the Meadows Center for Water and the Environment at Texas State University, says the lack of rainfall and unprecedented heat has caused aquifers in Texas – as well as statewide reservoir levels – to drop to levels reminiscent of the drought between 2009 and 2015. Listen to the interview by clicking the article title or picture above or read the transcript below. This transcript has been edited lightly for clarity: Texas Standard: How would you describe water supply conditions across the state right now? Robert Mace: Well, with the lack of rainfall and some unprecedented temperatures, we’re seeing aquifer levels drop, and we’re also seeing our statewide reservoir levels drop somewhat reminiscent of the drought we saw from 2009 to 2015. You mentioned groundwater across Texas, support water supply in some very populated parts of the state. Thinking about the Edwards Aquifer, the Trinity Aquifer, the Ogallala Aquifer – how are our ground water resources doing right now? Well, in Central Texas, and particularly the Edwards Aquifer, it’s an aquifer that has a lot of caves in it and fractures. It’s very responsive to the weather and very responsive to drought, unfortunately. And so we’ve seen water levels drop in those aquifers and we’ve seen spring flows as a response also drop. So, for example, Jacob’s Well, which is fed by the Trinity Aquifer, has recently stopped flowing. And then we’ve also seen Las Moras |

Springs stop flowing. San Felipe Springs out in Del Rio, which is fed by Edwards Aquifer, has kind of the lowest levels of flow in at least 50 years. And we’re also seeing Barton Springs, and San Marcos Springs where I work, not reached historic lows, but going deeper into the drought levels and requiring people to cut back usage in order to preserve the spring flows and the endangered species that live in them.

What efforts would you like to see? I mean, besides the just regular conservation that folks can do, and being mindful of their water use. Are there bigger efforts that the state needs to make to preserve our water resources for years to come? I think there’s things that can be done on an institutional level to conserve water. So, for example, using the built environment as a water supply, capturing air conditioning, condensate, which we generate a lot in Texas, capturing rainwater, reusing the wastewater. There’s a school in Wimberley that we refer to as the first warm water school in Texas, where, by capturing rainwater condensate, doing onsite wastewater treatment, they reduced their water footprint from the Trinity Aquifer by 90%. The City of Austin has done some very neat things with the main library. Similarly they also reduced the reliance on Colorado River water for that building by 80% to 90%. And then Austin also recently revealed a building scale wastewater treatment plant where they’re treating the wastewater that goes down the toilets, sinks the urinals, a treating and bringing it back in to flush urinals and flush toilets, thereby creating more water savings. It sounds like that ought to be conversations that we’re having at a broader level at this point then. Yes, I agree. And with the Texas population almost doubling every 50 years and just the easy water is gone for the most part. And so we need to be more creative and more strategic about where our water supplies are coming in the future, not only to make sure that you and I have water, but also that there’s water for the environment as well. |

Heat Wave Deepens Texas Drought

A series of 100-degree days have created worsening conditions for livestock and crop producers across the state, Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service agents report.

By Adam Russell, Texas A&M AgriLife Communications

July 14, 2022

July 14, 2022

|

A heat wave across the state is exacerbating the extreme drought conditions plaguing Texas agriculture.

Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service agents and regional specialists around the state have reported a wide range of issues related to triple-digit temperatures and worsening conditions for livestock and crop producers. There are reports of poor forage and growing conditions throughout the state, including failed to stunted plants and lower yield expectations on crops ranging from sorghum, cotton, peanuts and pecans. Livestock producers in drier areas of the state have been weaning and marketing calves earlier and culling herds deeper than usual. There are also reports of herd consolidations occurring. The main factor driving higher and earlier cattle sale volumes is poor spring forage production from lack of rainfall and the high cost of supplemental feed. Hay supplies are tightening and cuttings have been well below average in most parts of the state so far. Declining surface water and poor water quality in stock ponds and tanks is becoming a wider issue for many producers. The extent of drought is driving local governments to implement restrictions on activities, including water consumption and outdoor burning. Burn bans have been implemented by county commissioners’ courts in 206 Texas counties as of July 11, according to the Texas A&M Forest Service. Irrigation water for agriculture is also falling under use-restrictions that limit applications to crops like cotton and pecans due to below-normal water levels in reservoirs and aquifers that desperately need runoff rainfall to recharge. Reagan Noland, AgriLife Extension agronomist, San Angelo, said the high temperatures and dry soil are leading to widespread crop failures even in some irrigated fields. There are no water restrictions on wells that pull from the aquifer for agriculture in that area. Noland said his area had good rain until mid-August last year but received no appreciable rain between late October and late May. When the area did pick up a two-inch rain around May 22, Noland said high temperatures and wind left muddy fields powder dry within days. “I hoped the rain in late May would provide a decent opportunity to plant cotton, but it wasn’t enough. Our subsoil moisture was too depleted for any planting moisture to persist,” he said. “Some irrigated fields looked OK, but most dryland crop acres never established at all, or seedlings burned up in the heat.” Heat Wave Delivers 100-Degree DaysJohn Nielsen-Gammon, state climatologist in the Texas A&M College of Geosciences Department of Atmospheric Sciences, said much of Texas has been experiencing above-average temperatures for months. South and Central Texas has been exceptionally hot this year, he said. San Antonio recorded 32 days over 100 degrees so far. The previous record for 100-degree days by this time of year in the city was 20 days in 2009. College Station has experienced 23 days with 100-degree temperatures, which is also more than ever recorded. |

Statewide, the Big Bend region has seen 78 days of triple-digit temperatures. Other notable locations with 100-degree days include Cotulla with 62, Laredo with 57, Del Rio with 48, Abilene with 45, and San Angelo with 44.

San Angelo is almost on pace with 2011 for 100-degree days. The city recorded 46 days over 100 degrees by this time and ended that year with 100 days over 100 degrees, he said. Multiple factors aligned to produce the high temperatures Texas is experiencing this summer, he said, including the early arrival of high temperatures. Locations in much of the state recorded record or near-record May temperatures that were above typical June average temperatures. Above-average spring temperatures and drought conditions compounded environmental effects on summer temperatures. The lack of moisture means there is less evaporative cooling, and more of the sun’s energy heats the ground which heats the air. Nielsen-Gammon said the water temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico are also well above normal. Most spring and summer air circulates into the state from the Gulf, and warmer conditions there translate into warmer air as it moves through the state. Heat waves like the one Texas is experiencing are related to weather patterns that create a dome of high pressure over the state or to the north, he said. The pattern prevents the flow of moist, tropical air and instead delivers air that has been sitting over the state or other hot areas around Texas. No Relief In SightNielsen-Gammon expects summer temperatures to remain above normal as soils continue to lose moisture and retain heat. “Unfortunately, the very hottest temperatures typically occur later in the summer, so off hand, I don’t see any relief in the future,” Nielsen-Gammon said. “It looks dismal for the next couple of weeks.” Nielsen-Gammon said a looming tropical disturbance could deliver some moisture to Louisiana and southeast Texas, but most of the state is likely to remain dry and hot. According to U.S. drought monitor archives, 100% of Texas experienced at least abnormally dry conditions with almost 72% experiencing exceptional drought conditions. The 2011 drought conditions peaked in October when 88% of the state was exceptionally dry while 97% of the state was in extreme to exceptional drought. Almost 98% of Texas is abnormally dry, but only 46% of the state is experiencing extreme to exceptional drought and 16% of the state suffering exceptional drought, according to the drought monitor. But it is a hard sell to tell many agriculture producers and farmers across Texas that 2022 has been better. Much of the state has received some scattered rain since January, Nielsen-Gammon said, but a few areas have received less moisture than in 2011. Corsicana, for example, has received less than 20 inches of rainfall since Sept. 1, compared to nearly 25 inches over the same period in 2010-2011. “There are definitely people who would take issue with anyone saying conditions are better in 2022 than in 2011,” he said. “For some, the impacts are going to be worse.” |

Drought Conditions in Central Texas Could Have Disastrous Impact on Area Rivers: Slowing River Flows Make the Water Quicker to Evaporate.

By Alan Kozeluh

July 7, 2022

July 7, 2022

|

SAN ANTONIO — Central Texas is seeing the worst drought conditions it has seen in a decade. It’s causing rivers to slow to a crawl and the impact of that could be disastrous.

“We definitely have some concerns with where the water level’s going to get too later in the year, if we don't start getting some level of consistent rain,” said Shaun Donovan, Environmental Sciences Manager at the San Antonio River Authority. There are places in south Texas right now where the flow of the river all but stops. “There's been reports of the Frio River is at 0.0 CFS, so it's not flowing at all right now,” Donovan said. “There was a lot of concerns and issues with the Guadalupe River, especially above Canyon Lake where they can't control the flow.” According to the U.S. Drought Monitor, most of Bexar County is in drought level D3, that’s out of four. Historically, this level, classified as Extreme Drought, has meant an increased risk of wildfires, severe loss of plant and |

wildlife, and very low river flows. The last time Bexar County was this dry was during the drought of 2011, when the entire state was at D4 – Exceptional Drought.